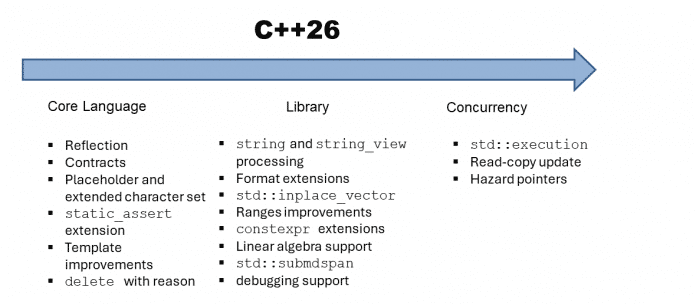

Following my overview of the new features in the C++26 library, I will now briefly introduce arithmetic extensions in another article.

Advertisement

Rainer Grimm has been working as a software architect, team and training manager for many years. He enjoys writing articles on the programming languages C++, Python and Haskell, but also frequently speaking at specialist conferences. On his blog Modern C++ he discusses his passion C++ in depth.

Apple presents the iPhone 16 Pro and iPhone 16 Pro Max, the crown jewels

Apple presents the iPhone 16 Pro and iPhone 16 Pro Max, the crown jewelsstd::submdspan

C++26 has a new subset std::submdspan.This is a subspan of an already existing span std::mdspan (C++23), which did not make it into C++23 itself.

Before I move on to C++26, I need to take a quick detour to C++23.

std::mdspan

A std::mdspan is a non-owning multidimensional view of a linked sequence of objects. The contiguous sequence of objects can be a simple C array, a pointer of sizeof, a std::array or a std::string This multidimensional view is often referred to as a multidimensional array.

The number of dimensions and the size of each dimension determine the size of a multidimensional array. The number of dimensions is called rank, and the size of each dimension is called extent. Size of std::mdspan Ist is the product of all dimensions that are not 0. On the elements of a std::mdspan can do it with multidimensional index operator () can be reached.

each dimension one std::mdspan a can steady Or dynamic range To pass. Static limit This means that their length is specified at compile time; dynamic range This means that its length is specified at runtime.

Thanks to class template argument derivation (CTAG) in C++17, the compiler can often automatically derive template arguments from the data types of the initialization:

// mdspan.cpp

#include

#include

#include

int main() {

std::vector myVec{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}; // (1)

std::mdspan m{myVec.data(), 2, 4}; // (2)

std::cout << "m.rank(): " << m.rank() << '\n'; // (4)

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < m.extent(0); ++i) { // (6)

for (std::size_t j = 0; j < m.extent(1); ++j) { // (7)

std::cout << m(i, j) << ' '; // (8)

}

std::cout << '\n';

}

std::cout << '\n';

std::mdspan m2{myVec.data(), 4, 2}; // (3)

std::cout << "m2.rank(): " << m2.rank() << '\n'; // (5)

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < m2.extent(0); ++i) {

for (std::size_t j = 0; j < m2.extent(1); ++j) {

std::cout << m2(i, j) << ' ';

}

std::cout << '\n';

}

} In this example, I apply class template argument deduction three times. In line (1) it is used for one std::vector One is used in lines (2) and (3) std::mdspan. The first two-dimensional array m It has the form (2,4), the second m2 The rank of both the rows (4) and (5) is of the form (4, 2). std::mdspan Demonstrated. It is easy to iterate through multidimensional arrays, thanks to the expansion of each dimension (lines 6 and 7) and the index operator in line (8).

This is where my tour of C++23 ends and I’m moving on to C++26 std::submdspan continued.

std::submdspan

Celebration std::submdspan was considered fundamentally important to the overall functionality of the mdspan However, due to time constraints during the review, it was initially removed again mdspan May be included in C++23.

Making One std::submdspan is simple. The first parameter is a mdspan xand the rest x.rank()-The parameters are slice specifiers, one for each dimension x. Slice specifiers describe what elements of the range are (0,x.extent(d)) Part of the returned multidimensional index space mdspan Are.

This results in the following basic signature:

template x, SliceArgs ... args); It has to be done E.rank() Even the sizeof...(SliceArgs) Happen.

Proposal P2630R4 The definition of a includes in addition std::submdspan some examples of one mdspan With rank 1.

int* ptr = ...;

int N = ...;

mdspan a(ptr, N);

// subspan of a single element

auto a_sub1 = submdspan(a, 1);

static_assert(decltype(a_sub1)::rank() == 0);

assert(&a_sub1() == &a(1));

// subrange

auto a_sub2 = submdspan(a, tuple{1, 4});

static_assert(decltype(a_sub2)::rank() == 1);

assert(&a_sub2(0) == &a(1));

assert(a_sub2.extent(0) == 3);

// subrange with stride

auto a_sub3 = submdspan(a, strided_slice{1, 7, 2});

static_assert(decltype(a_sub3)::rank() == 1);

assert(&a_sub3(0) == &a(1));

assert(&a_sub3(3) == &a(7));

assert(a_sub3.extent(0) == 4);

// full range

auto a_sub4 = submdspan(a, full_extent);

static_assert(decltype(a_sub4)::rank() == 1);

assert(a_sub4(0) == a(0));

assert(a_sub4.extent(0) == a.extent(0));The same rules apply in the case of multifunctional use:

int* ptr = ...;

int N0 = ..., N1 = ..., N2 = ..., N3 = ..., N4 = ...;

mdspan a(ptr, N0, N1, N2, N3, N4);

auto a_sub = submdspan(a,full_extent_t(), 3, strided_slice{2,N2-5, 2}, 4, tuple{3, N5-5});

// two integral specifiers so the rank is reduced by 2

static_assert(decltype(a_sub) == 3);

// 1st dimension is taking the whole extent

assert(a_sub.extent(0) == a.extent(0));

// the new 2nd dimension corresponds to the old 3rd dimension

assert(a_sub.extent(1) == (a.extent(2) - 5)/2);

assert(a_sub.stride(1) == a.stride(2)*2);

// the new 3rd dimension corresponds to the old 5th dimension

assert(a_sub.extent(2) == a.extent(4)-8);

assert(&a_sub(1,5,7) == &a(1, 3, 2+5*2, 4, 3+7));However, this is not the end of support for C++26.

– linear algebra

linalg There is a free interface to linear algebra based on BLAS (Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms). BLAS according to Wikipedia is A specification that defines a set of low-level routines for performing common linear algebra operations such as vector addition, scalar multiplication, dot product, linear combination, and matrix multiplication. They are the de facto standard for low-level routines in linear algebra libraries.

Proposal P1673R13 suggests an interface for that dense The linear algebra of the C++ standard library, which is based on dense Basic Linear Algebra Subroutines (BLAS). This corresponds to a subset of The BLAS Standard,

This linear algebra has been missing in the C++ community for a long time. As proposed, the following code snippet is the “Hello World” of linear algebra. It measures the elements of a 1-D-mdspan by a constant factor, first sequentially, then in parallel:

constexpr size_t N = 40;

std::vector x_vec(N);

mdspan x(x_vec.data(), N);

for(size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

x(i) = double(i);

}

linalg::scale(2.0, x); // x = 2.0 * x

linalg::scale(std::execution::par_unseq, 3.0, x);

for(size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

assert(x(i) == 6.0 * double(i));

} What will happen next?

The innovations in C++26 are not over yet. In my next post I will write about saturation arithmetic and concurrency support in C++26.

(Map)

BetterCode() Java 2024: Online Conference and Workshops on Java Innovations

BetterCode() Java 2024: Online Conference and Workshops on Java Innovations